Pistons are the unsung heroes of engines, transforming explosive force into mechanical motion that powers our world. These cylindrical components might seem simple at first glance, but they’re sophisticated engineering marvels that have evolved over centuries. When you turn your car’s ignition key, pistons spring into action, harnessing controlled explosions to propel you forward. These little powerhouses work tirelessly beneath the hood, enduring extreme temperatures and pressures while maintaining precision performance.

Understanding pistons isn’t just for mechanics and engineers – it’s valuable knowledge for anyone who relies on engines in daily life. From the car you drive to the lawnmower in your garage, pistons make it all possible. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what pistons are, their various types, essential components, and how they function within an engine system. Whether you’re a curious car owner or a student of mechanical engineering, this article will deepen your appreciation for these fundamental engine components.

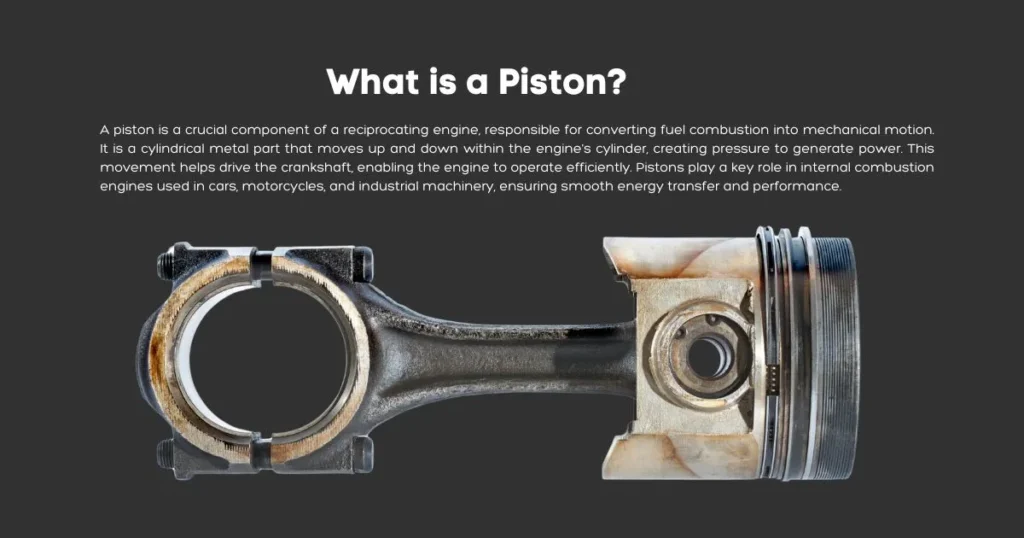

What is a Piston?

A piston is a cylindrical component that moves up and down within a cylinder, forming a crucial part of internal combustion engines and many other mechanical systems. It acts as a moving boundary that converts the energy from expanding gases into mechanical work through a connecting rod and crankshaft. The piston forms a seal against the cylinder walls, maintaining pressure and transferring force efficiently.

When fuel combusts in the cylinder, it creates a rapid expansion of gases. This expansion pushes against the piston head, forcing it downward. The piston then transfers this linear motion through the connecting rod to the crankshaft, which converts it into rotational motion. This rotation ultimately powers the vehicle’s wheels or other mechanical systems.

Pistons operate in extremely demanding conditions, withstanding thousands of explosions per minute while maintaining precise tolerances. They must be durable enough to handle temperatures that can exceed 2,000°F (1,093°C) and pressures of several thousand pounds per square inch. Despite these challenges, modern pistons perform reliably for hundreds of thousands of miles with proper maintenance.

Piston Materials and Composition

Modern pistons are primarily manufactured from aluminum alloys, though some specialized applications still use cast iron or steel. Aluminum has become the material of choice due to its excellent balance of strength, thermal conductivity, and light weight. The reduced mass of aluminum pistons helps engines achieve better fuel efficiency and performance by decreasing reciprocating mass.

These aluminum alloys are specially formulated to withstand the extreme conditions within an engine. They typically contain silicon (between 8-12%) to reduce thermal expansion and improve wear resistance. Other elements like copper, nickel, and magnesium are added to enhance strength and heat resistance. The exact composition varies depending on the engine application and manufacturer specifications.

Manufacturing processes for pistons have evolved dramatically over the years. Modern pistons are typically cast and then precisely machined to achieve the exact dimensions required. Some high-performance pistons are forged rather than cast, which provides greater strength but at a higher cost. Advanced coatings are often applied to reduce friction and improve durability, particularly in high-performance applications.

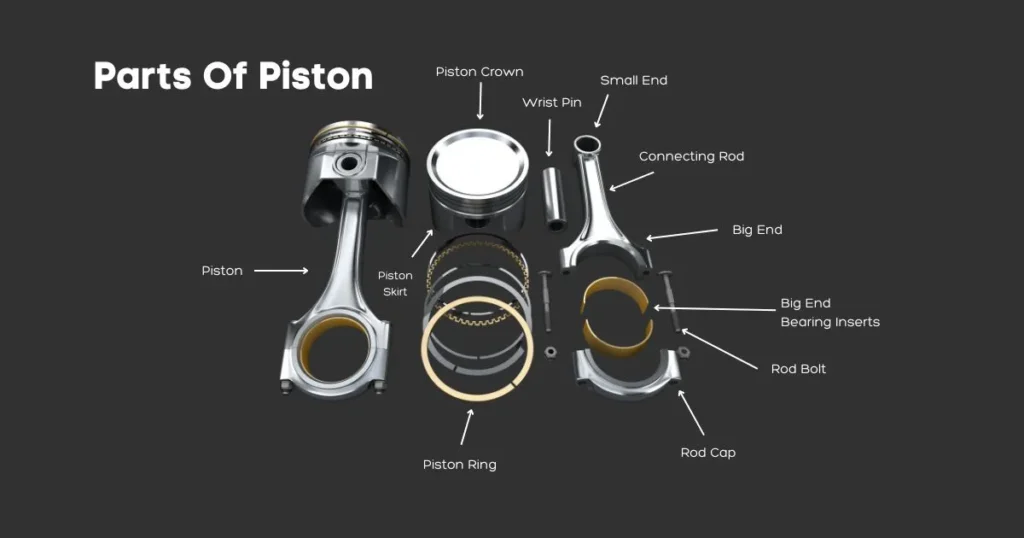

Piston Parts

Understanding the anatomy of a piston reveals the ingenious engineering behind this seemingly simple component. Each part serves a specific purpose, working in harmony to ensure efficient operation under extreme conditions. Let’s explore the primary components that make up a complete piston assembly.

- Piston Head/Crown

- Piston skirt

- Connecting rod

- Piston pin

- Piston rings

- Piston bearings

Piston Head/Crown

The piston head, also called the crown, is the top portion of the piston that directly faces the combustion chamber. It absorbs the brunt of the explosion’s force and heat during the combustion process. The design of the piston crown significantly impacts engine performance and efficiency.

Modern piston crowns come in various designs to optimize combustion efficiency and accommodate different engine configurations. Some feature valve reliefs – recessed areas that prevent contact with valves during operation. Others incorporate special shapes that enhance swirl and tumble of the air-fuel mixture for better combustion.

Engineers have developed sophisticated computer modeling techniques to optimize crown design for specific engine applications. These designs can increase power output, improve fuel efficiency, and reduce emissions by creating ideal combustion conditions. The crown must be thick enough to withstand combustion pressures while dissipating heat effectively to prevent detonation and piston failure.

Piston Skirt

The piston skirt is the lower portion of the piston that extends below the piston pin. It provides stability and guidance as the piston travels up and down in the cylinder. The skirt prevents the piston from rocking or tilting during operation, which would cause uneven wear and potentially lead to engine damage.

Modern pistons often feature skirts with specific designs to reduce friction and weight while maintaining structural integrity. Cam-ground skirts, for example, are deliberately manufactured with a slightly oval shape to accommodate thermal expansion during operation. As the piston heats up, it expands into a more circular shape, providing optimal cylinder contact.

Many high-performance pistons incorporate special coatings on the skirt to reduce friction and wear. These coatings, such as graphite or molybdenum disulfide, can significantly improve efficiency and extend engine life by reducing parasitic power losses due to friction.

Connecting Rod

While technically not part of the piston itself, the connecting rod is an essential component that works in conjunction with the piston. It connects the piston to the crankshaft, converting the piston’s reciprocating motion into the rotational motion of the crankshaft.

Connecting rods experience tremendous forces during engine operation, alternating between compression and tension as the piston moves through its cycle. They’re typically made from forged steel, though some high-performance applications use titanium or aluminum alloys to reduce weight.

The connecting rod attaches to the piston via the piston pin and to the crankshaft via a bearing surface. The design of this connection is crucial for engine durability and performance. Engineers must carefully consider factors such as rod length, weight, and strength to optimize engine characteristics.

Piston Pin

The piston pin (also called the wrist pin) is a hollow cylindrical component that connects the piston to the connecting rod. It creates a pivoting joint that allows the connecting rod to change angles as the crankshaft rotates while the piston moves strictly up and down.

Piston pins are typically made from hardened steel and must be precisely manufactured to withstand enormous forces. They’re usually hollow to reduce reciprocating mass while maintaining strength. The pin fits through a boss in the piston and can be secured in various ways, including press fits, interference fits, or with retaining clips.

The design of the piston pin and its bosses is critical for engine durability. Engineers must carefully balance weight reduction with structural strength to prevent failure under the extreme forces experienced during engine operation. In high-performance applications, special materials like titanium may be used to further reduce weight while maintaining strength.

Piston Rings

Piston rings are circular bands that fit into grooves cut around the piston’s outer diameter. These rings serve multiple critical functions: they seal the combustion chamber, control oil consumption, and transfer heat from the piston to the cylinder walls.

Most pistons feature three rings: the top compression ring, the second compression ring, and the oil control ring. The top compression ring primarily seals the combustion chamber, preventing high-pressure gases from escaping. The second compression ring provides additional sealing and helps direct oil downward. The oil control ring regulates oil distribution on cylinder walls, ensuring proper lubrication while preventing excessive oil consumption.

Piston rings are typically made from cast iron or steel, often with special coatings such as chrome, molybdenum, or nitride to improve durability and reduce friction. The precise design of these rings – including their face profiles, materials, and tension – is crucial for engine performance, efficiency, and longevity.

Piston Bearings

Piston bearings are precision components that reduce friction between moving parts in the piston assembly. The most critical bearing is located where the connecting rod attaches to the crankshaft, known as the rod bearing.

These bearings are typically made from materials like copper-lead alloys or aluminum with various coatings designed to withstand high loads and temperatures. They’re precision-manufactured to maintain a specific oil clearance – the gap that allows oil to flow between the bearing and the crankshaft journal.

Modern engine bearings incorporate sophisticated designs and materials to improve durability and reduce friction. Some feature micro-grooves that enhance oil circulation, while others use specialized coatings that can temporarily protect the bearing surface if oil pressure is lost or during engine startup when oil pressure is still building.

Primary Types of Pistons

Pistons come in various designs, each optimized for specific applications and engine types. The design differences primarily relate to the crown configuration, skirt design, and overall construction. Let’s explore the major types of pistons used in modern engines.

- Flat top pistons

- Dish Pistons

- Dome Pistons

Flat-Top Pistons

Flat-top pistons feature a flat crown surface that’s perpendicular to the cylinder walls. This straightforward design is common in many mass-produced engines due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. Flat-top pistons are particularly well-suited for engines with efficient combustion chamber designs in the cylinder head.

These pistons typically offer good durability and consistent performance across a wide range of operating conditions. Their simple design allows for efficient heat transfer and relatively straightforward manufacturing processes. Flat-top pistons are often used in engines with moderate compression ratios and where simplicity and reliability are prioritized over maximum performance.

Many modern flat-top pistons incorporate subtle design features to enhance performance. These might include slight valve reliefs to prevent interference with valves at high RPMs, or specific ring land designs to improve ring sealing. Despite their simple appearance, considerable engineering goes into optimizing flat-top pistons for specific engine applications.

Dome Pistons

Dome pistons feature a raised crown that extends into the combustion chamber. This design increases the compression ratio by reducing the combustion chamber volume. Higher compression ratios can improve thermal efficiency and power output, making dome pistons popular in naturally aspirated performance engines.

The dome shape also affects flame propagation during combustion, potentially increasing combustion efficiency when properly designed. The specific contour of the dome is engineered to work with the cylinder head design, sometimes incorporating valve reliefs to prevent interference.

Dome pistons are primarily used in high-performance naturally aspirated engines where maximum power output is the primary goal. However, they can present challenges in emissions-controlled applications, as the higher compression and altered combustion characteristics can increase certain emissions components.

Dish Pistons

Dish pistons feature a concave depression in the crown, creating a “dish” that increases the combustion chamber volume. This design is primarily used to lower the compression ratio, which can be beneficial in turbocharged or supercharged applications where excessive compression could lead to detonation.

The dish shape also influences the combustion process itself, affecting flame propagation and turbulence within the chamber. Engineers can fine-tune the dish design to optimize power delivery, emissions, and efficiency for specific engine configurations. The depth and shape of the dish are carefully calculated to achieve the desired compression ratio and combustion characteristics.

Dish pistons are common in high-performance forced induction engines, where controlled compression ratios are crucial for preventing detonation under boost. They’re also used in some emissions-focused engine designs where specific combustion characteristics help reduce pollutants.

Multiple Types of Pistons

While crown design creates the primary categories of pistons (flat-top, dish, and dome), there are also several specialized piston designs that address specific engine configurations and applications. Let’s explore these variations and understand their unique characteristics.

- Trunk pistons

- Slipper pistons

- Crosshead pistons

- Racing Pistons

- Deflector pistons

Trunk Pistons

Trunk pistons are the most common design found in automotive and small engine applications. They feature an extended skirt that serves as both a guide for piston movement and as the bearing surface against the cylinder wall. This integrated design simplifies the engine’s construction by eliminating the need for a separate crosshead.

The longer skirt of trunk pistons provides excellent stability during operation, preventing the piston from rocking in the cylinder. This design works well for relatively high-speed engines with moderate loads, making it ideal for passenger vehicles and light machinery. The skirt length can be optimized based on the engine’s operating characteristics.

Modern trunk pistons often incorporate design features to reduce weight and friction while maintaining durability. These include strategically placed reinforcement ribs, skirt profiles tailored for minimal friction, and reduced skirt areas (partial skirts) where full cylinder contact isn’t necessary for proper guidance.

Slipper Pistons

Slipper pistons represent a compromise between full trunk pistons and crosshead designs. They feature partial skirts with cutaways on non-thrust surfaces, reducing weight and friction while maintaining adequate guidance on the thrust surfaces where lateral forces are highest.

These pistons are particularly popular in high-performance motorcycle engines and some racing applications where minimizing reciprocating mass is crucial for high-RPM operation. By removing skirt material from areas that don’t bear significant loads, slipper pistons can improve performance without sacrificing reliability.

The design of slipper pistons requires careful analysis of the forces involved during engine operation. Engineers must determine exactly which portions of the skirt can be removed without compromising stability. Advanced computer modeling has enabled increasingly optimized designs that precisely balance weight reduction with durability requirements.

Crosshead Pistons

Crosshead pistons are primarily used in large industrial engines and marine applications where extreme loads and durability are paramount. Unlike trunk pistons, crosshead pistons work with a separate crosshead component that guides the connecting rod and absorbs side forces generated during operation.

This design separates the sealing function from the guiding function, allowing each component to be optimized for its specific role. The piston itself can focus entirely on sealing the combustion chamber and transferring force, while the crosshead handles the lateral forces that would typically cause wear on a trunk piston’s skirt.

Crosshead pistons typically have shorter skirts since they don’t need to provide guidance. This reduces weight and friction while still maintaining excellent durability under high loads. They’re particularly advantageous in low-speed, high-torque applications like large ship engines and industrial power generation.

Racing Pistons

Racing pistons represent the cutting edge of piston technology, incorporating advanced materials, sophisticated designs, and specialized manufacturing techniques to maximize performance under extreme conditions. These pistons prioritize power output and high-RPM capability, sometimes at the expense of longevity.

Materials used in racing pistons often include forged aluminum alloys with higher silicon content for improved strength and heat resistance. Some racing pistons incorporate exotic materials like titanium for connecting hardware or ceramic thermal barriers on crown surfaces to manage heat more effectively.

Design features unique to racing pistons include extensive strengthening ribs, specialized ring packages with thinner rings for reduced friction, gas ports to enhance ring sealing under high pressures, and precisely calculated crown shapes to optimize combustion for maximum power output. The exact specifications are tailored to the specific racing application, with different designs for drag racing, endurance racing, and other motorsport categories.

Deflector Pistons

Deflector pistons feature a specially shaped crown designed to direct the incoming air-fuel mixture in two-stroke engines. The deflector – a raised portion on one side of the crown – helps prevent the fresh mixture from flowing directly out the exhaust port during the scavenging process.

This design was common in older two-stroke engines before more sophisticated port and transfer designs were developed. The deflector creates turbulence and directs the incoming charge upward, away from the exhaust port, improving efficiency and reducing fuel waste in simple two-stroke configurations.

Modern two-stroke engines typically use more advanced port arrangements and reed valve systems rather than deflector pistons. However, the principle of controlling gas flow through crown design remains relevant in specialized applications and continues to influence advanced combustion chamber designs.

Characteristics of a Piston

Modern pistons incorporate numerous design characteristics that optimize performance, durability, and efficiency. These features represent decades of engineering development and continuous refinement to meet increasingly demanding requirements.

Thermal expansion control is a critical characteristic of piston design. As pistons heat up during operation, they expand – but not uniformly. Engineers account for this by designing pistons with specific dimensions and profiles that achieve optimal clearances when at operating temperature. This might include cam-ground profiles or tapered skirts that appear slightly oval when cold but become more circular at operating temperature.

Weight reduction is another key characteristic, particularly in high-performance applications. Lighter pistons reduce reciprocating mass, allowing engines to accelerate more quickly and reach higher RPMs with less stress on components. Weight-saving features might include shorter skirts, internal ribbing instead of solid sections, and strategic material removal in non-critical areas.

Noise reduction has become increasingly important in modern engine design. Pistons can contribute to engine noise through slap (the sound of the piston rocking and hitting the cylinder wall) and general operation. Features like offset piston pins, specialized skirt designs, and precision manufacturing tolerances help minimize these noise sources, contributing to quieter engine operation.

Piston Working

The primary function of a piston is to convert the energy of expanding gases into mechanical motion. This seemingly simple task involves a complex interplay of forces, temperatures, and precision engineering. Let’s examine how pistons perform their crucial role in the engine cycle.

In a four-stroke car engine, the piston goes through four distinct phases: intake, compression, power, and exhaust. During the intake stroke, the piston moves downward, creating a vacuum that draws the air-fuel mixture into the cylinder. The compression stroke follows, with the piston moving upward to compress this mixture, increasing its temperature and pressure for more efficient combustion.

The power stroke occurs when the compressed mixture ignites, either from a spark plug in gasoline engines or from compression heat in diesel engines. The resulting explosion forces the piston downward, generating the mechanical energy that ultimately propels the vehicle. Finally, during the exhaust stroke, the piston moves upward again, pushing the spent gases out through the exhaust valve.

Throughout this cycle, the piston maintains a critical seal against the cylinder walls via its rings, preventing pressure loss while allowing the piston to move freely. It also transfers heat from the combustion process to the cylinder walls and eventually to the cooling system, preventing overheating of the engine components.

Applications and Uses of Pistons

Pistons find application across an incredibly diverse range of machinery and equipment. Their versatility and effectiveness in converting pressure to motion make them fundamental components in numerous systems beyond traditional vehicle engines.

In automotive applications, pistons are the heart of both gasoline and diesel engines. They endure different operating conditions depending on the engine type – gasoline engines typically operate at higher RPMs but lower pressures, while diesel engines generate greater pressures but often at lower RPMs. Specialized piston designs address these specific requirements.

Industrial machinery relies heavily on pistons, both in engines and in hydraulic systems. Large industrial engines in generators, pumps, and heavy equipment feature robust piston designs optimized for longevity and reliability. Hydraulic systems use pistons to convert fluid pressure into linear motion, enabling powerful and precise movement in equipment ranging from construction machinery to manufacturing robots.

Marine applications present unique challenges for piston design. Ship engines often operate continuously for weeks or months, requiring exceptional durability and reliability. These engines typically use crosshead pistons as mentioned earlier, separating the guiding and sealing functions to optimize performance under constant heavy loads.

Aviation represents another specialized application area. Aircraft pistons must deliver exceptional reliability while minimizing weight. They typically operate at relatively constant RPMs but must handle rapid changes in load and altitude. Advanced materials and manufacturing techniques ensure these pistons maintain performance across varying atmospheric conditions.

Benefits of Piston

The piston engine design offers numerous advantages that have ensured its continued dominance in many applications despite the development of alternative technologies. Understanding these benefits helps explain why piston engines remain the powerplant of choice for most vehicles and many other applications.

Simplicity and reliability stand out as primary advantages. The basic operating principle of piston engines has remained essentially unchanged for over a century, allowing for extensive refinement and optimization. This maturity translates to exceptional reliability when properly maintained, with modern engines routinely operating for hundreds of thousands of miles before requiring major service.

Adaptability represents another significant advantage. Piston engines can be designed to run on various fuels including gasoline, diesel, natural gas, propane, and even biofuels with relatively minor modifications. This fuel flexibility provides practical options across different markets and applications worldwide.

Cost-effectiveness in manufacturing makes piston engines economically viable for mass production. The manufacturing processes for pistons and related components have been refined over decades, with economies of scale driving down costs. Despite their precision engineering, modern pistons can be produced efficiently in large volumes.

Power density – the amount of power generated relative to engine size and weight – has improved dramatically in modern piston engines. Technological advancements like direct injection, variable valve timing, and turbocharging have pushed the boundaries of what’s possible, allowing smaller, lighter engines to produce power previously requiring much larger displacements.

Disadvantages of Piston

Despite their widespread use and continuous improvement, piston engines do have inherent limitations and disadvantages that engineers must work around. These factors contribute to ongoing research into alternative power sources for certain applications.

Efficiency limitations exist inherent to the design. Even the most advanced piston engines convert only about 30-40% of fuel energy into useful mechanical work, with the remainder lost as heat and friction. This thermodynamic limit presents a challenge as efficiency standards become increasingly stringent worldwide.

Emissions production remains a concern despite significant improvements. The combustion process inevitably generates pollutants including carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter. While modern engines have dramatically reduced these emissions through advanced controls and aftertreatment systems, completely eliminating them remains challenging within the piston engine paradigm.

Complexity has increased substantially as engineers have worked to improve efficiency and reduce emissions. Modern engines incorporate sophisticated electronic controls, variable geometry components, and precise fuel delivery systems that add cost and potential failure points. This increasing complexity can impact long-term reliability and maintenance costs.

NVH (Noise, Vibration, and Harshness) characteristics present ongoing challenges. The reciprocating nature of pistons creates inherent vibrations that must be managed through balancing, dampening systems, and precise manufacturing. While modern engines are dramatically smoother than their predecessors, they still cannot match the inherent smoothness of some alternative designs like electric motors.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of a piston in an engine?

A piston’s primary function is to convert the energy from expanding gases during combustion into mechanical motion. It forms a moving seal within the cylinder, capturing the force of the explosion and transferring it through the connecting rod to the crankshaft, which ultimately powers the vehicle or machinery. This conversion from linear to rotational motion is fundamental to internal combustion engine operation.

Are aluminum or steel pistons better for high-performance applications?

Aluminum pistons are generally preferred in high-performance applications due to their lighter weight, which allows for higher RPM operation and reduced reciprocating mass. Modern aluminum alloys with high silicon content offer excellent strength and thermal properties. Steel pistons provide superior durability and thermal stability but at a significant weight penalty, making them better suited for extreme duty applications rather than performance engines focusing on responsiveness and acceleration.

How do piston rings prevent oil from entering the combustion chamber?

Piston rings prevent oil from entering the combustion chamber through a three-ring system. The top and second compression rings primarily seal combustion gases, while the oil control ring specifically manages oil distribution. The oil ring features small holes or slots that allow excess oil to drain back to the crankcase while maintaining just enough oil on cylinder walls for lubrication. This carefully engineered system allows for proper lubrication without excessive oil consumption or combustion.

What causes piston slap and how can it be prevented?

Piston slap occurs when the piston rocks slightly within the cylinder, causing the skirt to impact the cylinder wall. This creates a distinctive knocking sound, particularly noticeable in cold engines. It’s typically caused by excessive piston-to-wall clearance, worn cylinders, or improper piston design. Prevention includes using pistons with offset pins to control rocking motion, maintaining proper operating temperatures, ensuring correct piston-to-wall clearances during building, and using pistons with anti-slap skirt designs specifically engineered to minimize this issue.

Can damaged pistons be repaired, or must they always be replaced?

Damaged pistons nearly always require replacement rather than repair. The precision tolerances, specialized materials, and critical nature of pistons mean that repairs rarely restore the original specifications and reliability. Minor damage like light scuffing might be addressed during rebuilding by honing cylinders and installing new rings, but pistons with cracks, broken ring lands, melted areas, or significant scoring should always be replaced. The potential consequences of piston failure make replacement the safer and more cost-effective long-term solution.

How have pistons evolved to improve fuel efficiency in modern engines?

Pistons have evolved significantly to improve fuel efficiency through numerous innovations. Modern designs feature reduced weight to decrease reciprocating mass and mechanical losses. Specialized coatings minimize friction between pistons and cylinder walls. Advanced crown designs optimize combustion chamber shape for better fuel burning. Shorter skirts reduce contact area while maintaining stability. Improved ring packages enhance sealing while reducing tension and friction. Together with complementary engine technologies like direct injection and variable valve timing, these piston developments have contributed substantially to the remarkable efficiency gains in contemporary engines.